Content:

1. Definition

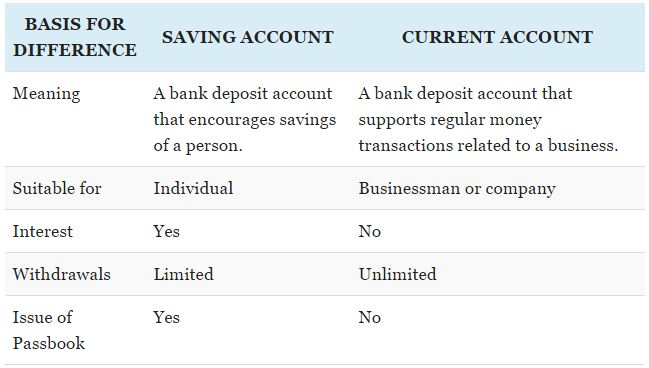

2. Comparison Chart

3. Key Differences

4. Similarities

1. Definition

Saving Account

Savings Account is the most common type of deposit account. An account held with a commercial bank, for encouraging savings and investments is known as a Saving Bank Account. A savings account provides an array of facilities like ATM cum Debit Card facility with different variants, calculation of interest on a daily basis, internet banking, mobile banking, online money transfer, etc.

The account can be opened by any Individual, Agencies or institutions (if they are registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860). A Pvt. Ltd and a Ltd. company are not allowed to open a savings account.

Current Account

A deposit account maintained with any commercial bank, for supporting frequent money transactions is known as Current Account. A plethora of facilities is provided to you, when you opt for a current account like payment on standing instructions, transfers, overdraft facility, direct debits, no limit on the number of withdrawals/deposits, Internet Banking, etc.

This type of account fulfills the very need of an organization that requires frequent money transfers in its day-to-day activity.

An Individual could open this type of account, Hindu Undivided Family (HUF), Firm, Company, etc. Account maintenance charges are applicable as per the bank rules. The current account is also known as checking account or a transactional account.

2. Comparison Chart

3. Key Differences

2. Saving Account is ideal for salaried people because of regular monthly savings. Conversely, Current Account is perfect for businesspeople because of the day to day money transactions.

3. There is a restriction on the number of monthly transactions, in the case of a savings account. There is no such cap for a Current Account.

4. The primary difference between them is current account is non-interest bearing whereas savings account offers interest on a daily basis.

4. Similarities

2. Internet Banking Facility

3. Multicity Cheque Facility

4. Nomination facility

5. Conclusion

We have discussed in detail about both the entities, and it is quite clear that the two are important in place. If we talk about the major difference between them, it is the number of transactions – withdrawal or deposit.